Transaction Architecture

|

|---|

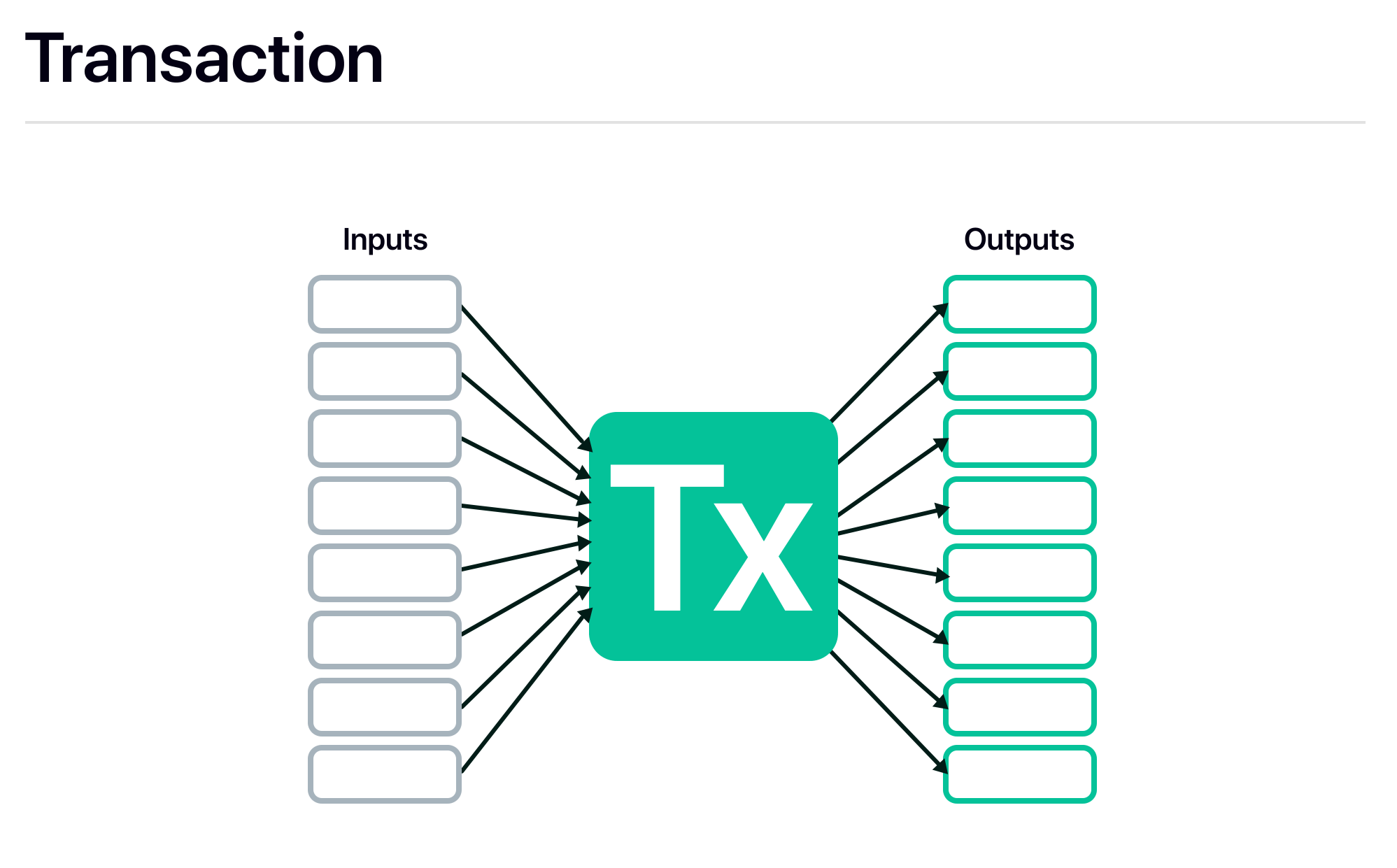

| A transaction with up to eight inputs and eight outputs. |

A transaction in Fuel specifies a state transition: inputs tell which state elements are consumed and outputs tell which state elements are produced. As with any UTXO-based system, each state element can only be produced and consumed at most once. Modeling the rollup chain's state as a key-value store, this means that keys can never be re-used, and keys commit to values in some way.

Note: Up to eight inputs and outputs are allowed per transaction, to keep the worst-case cost of fraud proofs low while simultaneously enabling a number of applications that require multiple inputs or outputs.

Each input specifies the state element to spend, and unlocks it. For plain UTXOs and deposits, this is the UTXO/deposit ID and a valid digital signature. For HTLC UTXOs, this is the UTXO ID and a preimage (if using the hashlock spending condition) and a valid digital signature.

Each output specifies the new state element to produce (including amounts, token type, etc.), and its spending conditions (recipient address, timelock and hashlock).

Transactions can be validated statelessly, and the state database only needs to be checked for the existence of each consumed state element. In addition, there is no inherent limitation on which accounts sign a transaction, so a transaction can represent an atomic interaction between more than one user (e.g. an on-chain atomic exchange).

The transaction ID (a unique identifier for each transaction) is computed as the EIP-712 hash of the hash of the transaction data without witnesses. We will see in the next section why excluding witness data has some nice properties.

Inputs: Witnesses and Metadata

|

|---|

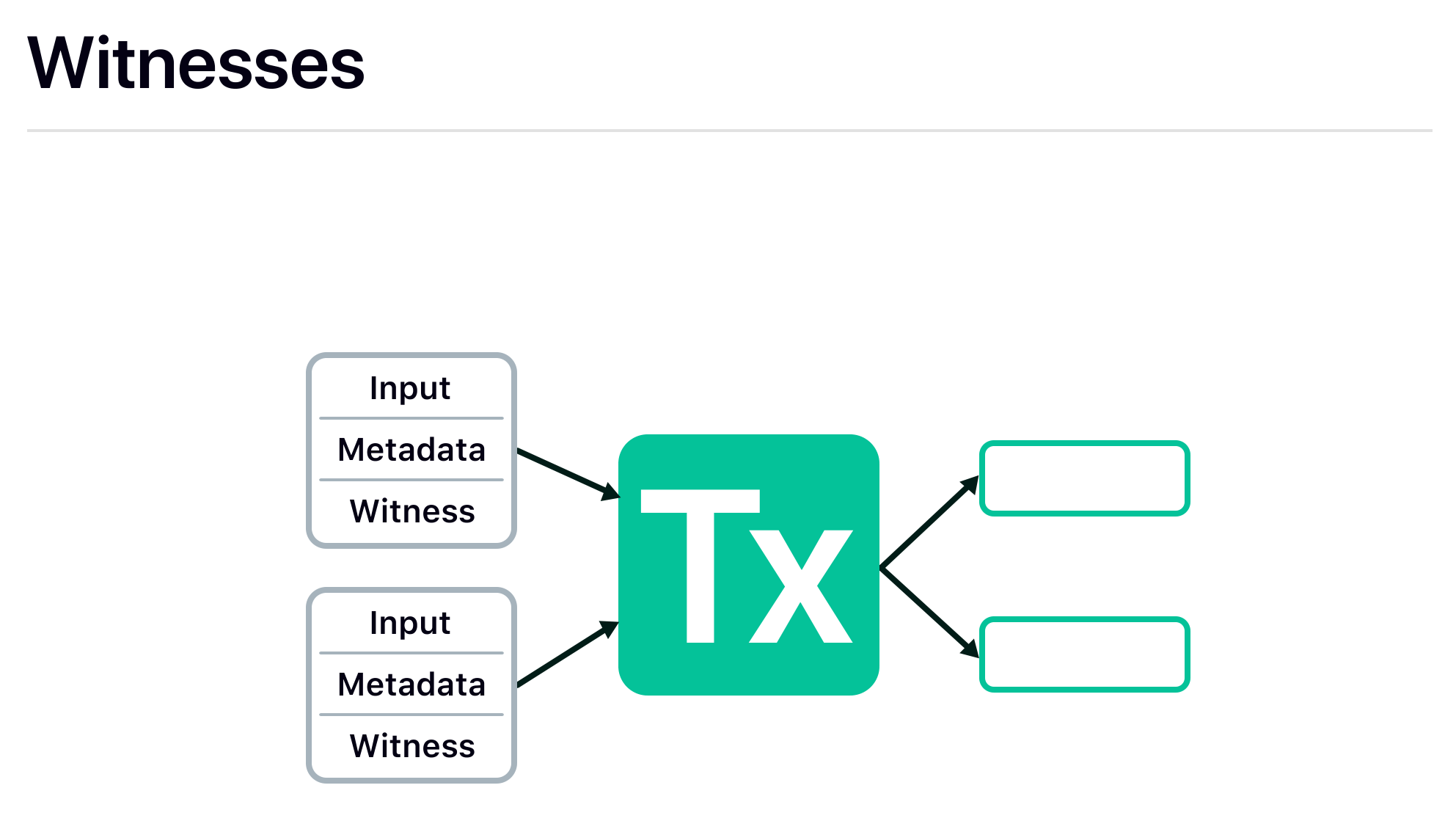

| Input witness and metadata. |

Each input is linked to a witness (generalization of a digital signature) and metadata.

Witnesses are either a digital signature, or an authorization from a smart contract on Ethereum (e.g. a smart contract wallet can be used to authorize Fuel transactions). In either case, authorization is performed on a transaction ID (as the in previous section, the non-witness transaction data), i.e. signatures are over the transaction ID.

Note: Signing over the transaction ID means that the transaction only has to be hashed once when verified, regardless of the number of inputs or outputs. This avoids the quadratic hashing issue seen in Bitcoin.

Each input specifies a state element to consume (i.e. a UTXO ID, or a deposit ID), which is a 32-byte hash. This value is part of the non-witness transaction data, and is signed over. However, when posting transactions on Ethereum, explicit state element identifiers are stripped and replaced by more compact metadata, which "point" to a unique entry in the ledger (or a deposit). In other words, metadata will point to an exact output in the totally ordered outputs, transactions, roots, and blocks.

Note: Given the one-to-one mapping between ledger entries and state element identifiers, it is easy to show the state element produced by an exact entry with a simple inclusion proof, leveraging the property that computing state element identifiers is a stateless operation.

Note: Extending the above, transaction IDs are not immediately obvious with only the data posted to Ethereum, since state element identifiers are missing. However, they can be proven, and the transaction IDs computed, with inclusion proofs for the entires pointed to by metadata.

Segregated Witnesses

|

|---|

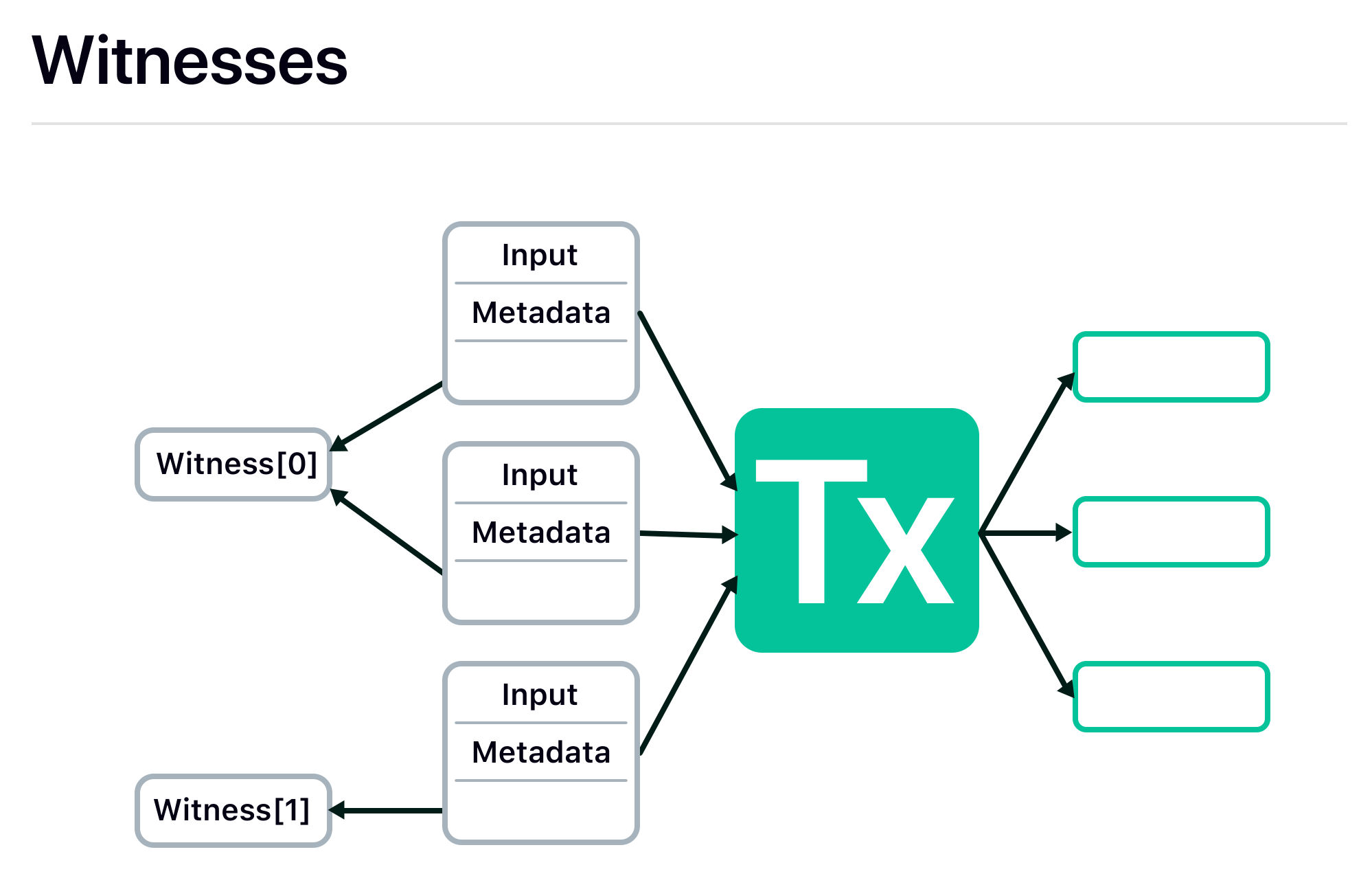

| Segregated witnesses. |

Fuel is designed with a form of segregated witness, where witness data is not bundled with inputs. While the previous sections provided intuition, they did not precisely describe where witnesses are placed in transactions.

Each input actually specifies a witness index that authorizes spending the referenced state element. This means that multiple inputs could use the same witness, which greatly reduces the cost of spending multiple state elements owned by the same account.

Simple Send Example

|

|---|

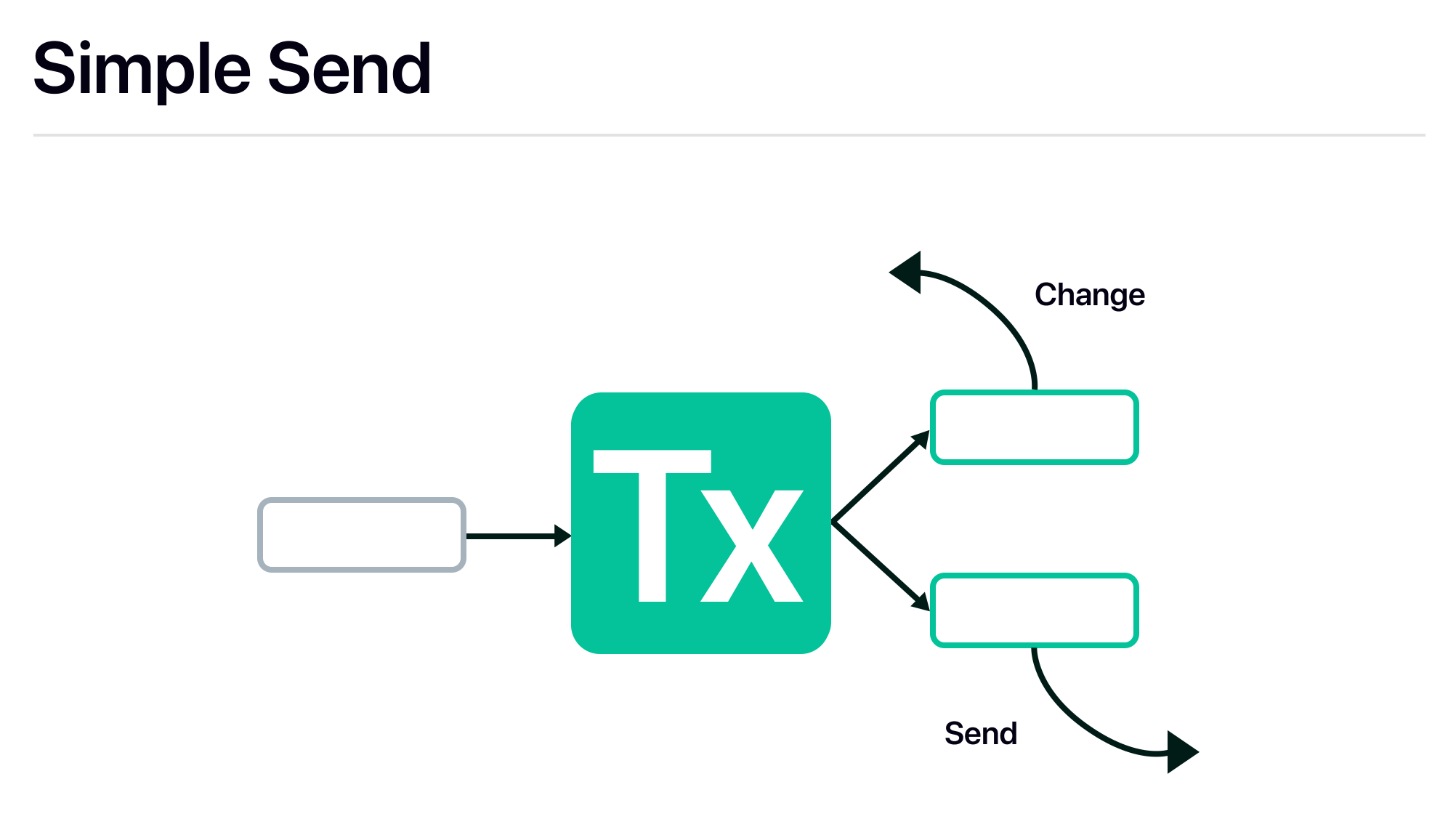

| A simple send. |

As an example, the above is a simple one-input two-output simple send. One output is returned to the sender as change (there is no special change output type, so it looks like any other output). The other is sent to the recipient.